Masjid Al-Haram features over 200 gates, but five main gates (King Abdulaziz, King Fahd, King Abdullah, Bab Umrah, Bab Al-Fath) with prominent minarets serve as key entry points to the Mataf (Kaaba area), regulating pilgrim flow for Tawaf and Umrah, with each gate named after Islamic history, people, or places, providing direct access to prayer areas or escalators for the central rituals. Navigating these gates, marked with names and numbers, is crucial for avoiding confusion, especially during peak times, as they offer access to the central Kaaba, Zamzam Well, and the Sa’i area.

If you want the best gate for Umrah pilgrims, use King Abdulaziz Gate, King Fahd Gate, or Bab Al-Umrah, because these lead closest to the Mataf, where your tawaf begins. They are wide, easy to find, and close to the Clock Tower.

Masjid Al-Haram has over 262 gates today (Madain Project, 2023). Each gate has a purpose. Some guide you straight to prayer. Others take you to Sa’i. Some carry centuries of history.

This is your complete Masjid Al-Haram gates guide, so you feel confident before arriving from the UK.

A Quick Look at the Mosque With 262 Gates

In early Islamic history, there were no walls and no gates. The Mataf was open to the sky. Pilgrims walked in freely from all directions.

After major Saudi expansions, especially the King Abdullah Expansion, one of the largest mosque projects in the world, the number increased to around 262 gates, including 13 disability-friendly gates (Madain Project & General Authority for Statistics KSA).

And each gate does something simple but important: It helps millions of pilgrims move safely and calmly.

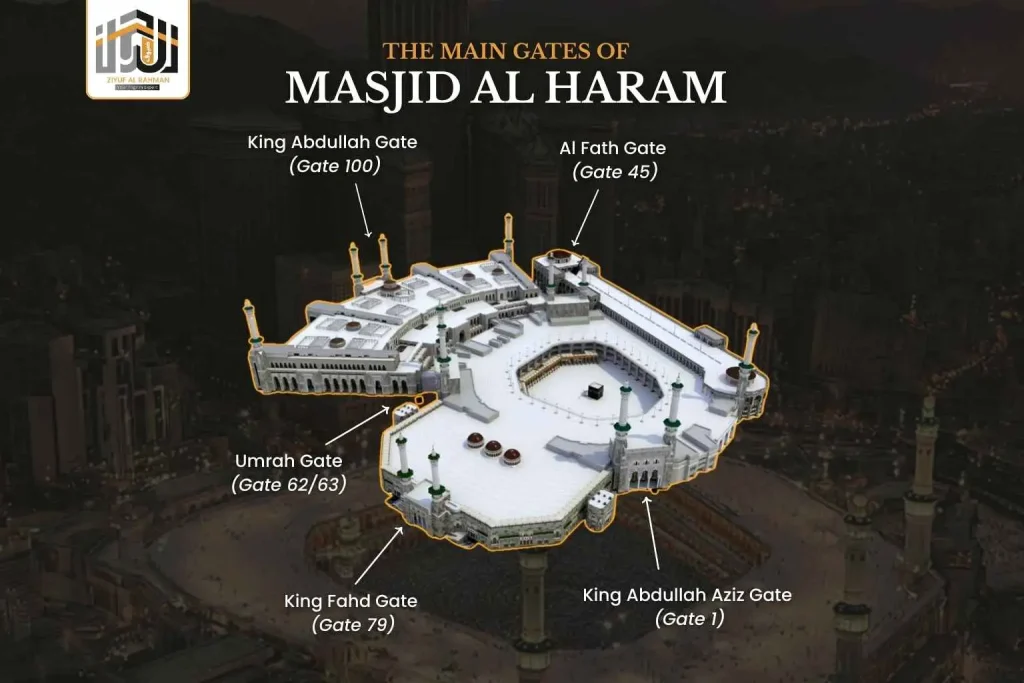

The Main Gates of Masjid Al-Haram That Shape Every Pilgrim’s First Moment

These five gates are used by most visitors. They set the tone for the journey ahead and appear in almost every list, every memory, and every prayer whispered before stepping inside.

King Abdulaziz Gate (Gate 1)

If Masjid Al-Haram had a front door, this would be it. The King Abdulaziz Gate rises tall on the western side, catching your eye the way a landmark does when it knows it’s important. The design is modern and square, a break from the softer Ottoman curves you see elsewhere. But its strength lies not in its shape; it lies in how direct it is.

Walk through this gate, and within moments, the Mataf opens up before you. The Kaaba appears in a way that makes even first-time pilgrims feel grounded. UK travellers staying near Ajyad or the Clock Tower almost always choose this gate, because it behaves like a promise: “I’ll take you straight where you need to go.”

King Fahd Gate (Gate 79)

Some gates are practical. Some are beautiful. King Fahd Gate manages to be both. Located near the Clock Tower, this gate was built during the second Saudi expansion and carries the tall, proud posture of two minarets standing guard. The moment you step inside, the world widens. Bright marble, open corridors, and most importantly, escalators.

For many older pilgrims from the UK, this is the gate that makes their Umrah possible. Escalators mean less strain, less worry, and more confidence. The gate leads to the outer prayer areas and then naturally flows toward the Mataf. This is why travel groups consistently list it in their top recommendations for the best gate for Umrah pilgrims who need easy movement or prefer avoiding steep stairways.

King Abdullah Gate (Gate 100)

This gate is enormous. A modern marvel. A glimpse into the future of Masjid Al-Haram. Built as part of the King Abdullah expansion, the largest expansion in the mosque’s history, this gate is defined by its vast scale and cooling systems designed for heavy crowds.

Unlike King Abdulaziz Gate, which gives direct access to the Kaaba, King Abdullah Gate offers space, wide corridors, open airflow, and long straight walkways that make it perfect for managing peak crowds. It’s not the closest route for tawaf, but it is one of the most organised. And in a crowd of thousands, organisation is mercy.

Bab Al-Fatah (Gate 45)

This is where faith meets memory. Bab Al-Fatah is believed to be the gate through which Prophet Muhammad ﷺ entered during the Conquest of Makkah. The very name, “Gate of Victory”, carries a sense of walking in the footsteps of something greater than yourself.

Located on the southern side, this gate leads toward the Mataf, though with a slightly longer walk than Bab Al-Umrah or King Abdulaziz Gate. And yet, many pilgrims choose it not for convenience but for connection. It feels like an entrance that remembers its history.

Bab Al-Umrah (Gates 62–63)

If convenience were a doorway, it would be Bab Al-Umrah. Located on the north-western side, this gate gives one of the closest entries to the Mataf. You walk in, take a few steps, and the Kaaba appears without delay.

When travel groups from the UK talk about the best gate for Umrah pilgrims, this gate always makes the list, often at the top. You use less energy, avoid complicated navigation, and reach tawaf with a steady heart. For families, elderly travellers, and first-time pilgrims, this gate feels like the easiest beginning to the journey.

Bab Ajyad (Gate 5)

Bab Ajyad sits quietly on the south-eastern side of Masjid Al-Haram, named after the deep Ajyad valleys that once shaped the city’s older neighbourhoods. It isn’t a dramatic gate; it doesn’t rise high or shine as brightly as others. But it behaves the way a good side door does, humble, useful, and dependable. As you approach it, you notice the steady flow of pilgrims, many heading toward the escalators that connect to the upper floors.

Bab Bilal (Gate 6)

Named after Bilal ibn Rabah (RA), the first mu’azzin of Islam, this gate carries a soft sense of honour. You feel it the moment you stand before its modest shape. Bab Bilal sits on the southern side of the mosque, close to older residential routes once used by Makkan families. It was built during the first Saudi expansion and remains a gentle reminder of a companion whose voice once carried across early Medina.

Bab Hunain (Gate 9)

Bab Hunain is named after the valley of Hunayn, where an early Muslim battle was fought. The gate lies between Bab Bilal and Bab Ismail, partially hidden today because escalators were installed in front of it during development works. In a way, this entrance behaves like a memory, still present, still meaningful, yet overshadowed by modern needs.

Bab Ismail (Gate 10)

Named after Prophet Ismail (AS), this gate sits humbly on the southern stretch of the mosque. It isn’t a large gate, nor does it carry the architectural drama of the big five. But its presence is symbolic. It stands quietly among other southern gates, offering an uncomplicated route for pilgrims walking in from side streets or less crowded pathways.

Bab Safa (Gate 12)

If you’re heading for Sa’i, this is your landmark. Bab Safa is one of the central gates in the Haram because it brings you directly to the Safa starting point, the beginning of the walk between Safa and Marwah. It has escalators connecting the lower and upper Sa’i floors, making it especially helpful during busy seasons. It even has scooter services for elderly or mobility-limited pilgrims, something UK visitors often appreciate.

Bab an-Nabi (Gate 14)

Bab an-Nabi, “The Gate of the Prophet”, is named in honour of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. Located on the eastern side near the Sa’i gallery, this gate blends symbolic value with practical access. It sits close to the historical routes that once connected Makkah’s early neighbourhoods, making its name feel fitting, as if it quietly honours the footsteps that once crossed this land.

Bab Dar ul-Arqam (Gate 16)

This gate is named after the home of Dar al-Arqam, where early Muslims gathered secretly to learn Islam before it became publicly accepted in Makkah. There is a quiet dignity in that history, and the gate carries it well. Bab Dar ul-Arqam leads to escalators that connect to the upper Sa’i floors and offers a smooth flow of movement away from the main crowds.

Bab Ali (Gate 17)

Bab Ali is named after Ali ibn Abi Talib (RA), the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet ﷺ. It lies on the eastern edge of the Haram and provides access to the Ramal area of Sa’i. Historically, this gate had several older versions and even different names depending on the era, but today it stands as a practical, functional part of the mosque.

Bab Abbas (Gate 20)

Bab Abbas is named after Abbas ibn Abdul Muttalib (RA), the uncle of the Prophet ﷺ. It is a three-portal gate, meaning one main arch sits between two smaller ones. This gives it balance and symmetry, a subtle architectural rhythm that you notice more with your heart than your eyes.

Bab Bani Hashim (Gate 21)

Named after Bani Hashim, the Prophet’s noble tribe, this gate carries heritage in its name. It is a bridge-style gate, meaning it connects different levels of the mosque. Its placement near other Sa’i-related gates gives it natural importance. Pilgrims often appreciate it for its simplicity, it exists to keep movement smooth.

Bab Bani Shaibah (Gate 22 – Modern)

This gate carries one of the oldest names in Masjid Al-Haram. The original Bani Shaibah arch, a free-standing stone gate, once stood close to the Kaaba, marking where the tribe of Shaybah lived. It appeared in many early Islamic texts before being removed during expansions to increase space for the Mataf.

Bab Marwah (Gate 23)

Bab Marwah is the natural counterpart to Bab Safa, marking the end of the Sa’i journey. It is one of the largest gates in this section of the mosque and includes escalators that take pilgrims between levels. After completing Sa’i, a ritual that often brings tears of gratitude, exiting through Bab Marwah feels like stepping out of a story and back into the world.

Bab Muda’a (Gate 25)

Bab Muda’a sits close to the lower Sa’i floor, and that’s what gives it its quiet usefulness. It’s not loud or dramatic, and you rarely see it in photos, but pilgrims who enter through here often describe the same feeling, “It’s easy.” The flow is steady, the walk is short, and you reach the Sa’i corridor without the swirl of heavier crowds.

Bab Arafat (Gate 35)

Named after Mount Arafat, this gate carries a quiet symbolism of the place where pilgrims stand on the most important day of Hajj. Bab Arafat sits along the eastern edge of the Haram, and it tends to attract people who prefer a slower approach into the mosque.

Bab Umar (Gate 49)

Bab Umar is named after Umar ibn al-Khattab (RA), and the gate mirrors his known qualities, straightforward, strong, and dependable. It isn’t decorated or pushed into the spotlight, but pilgrims who walk in from the south side often appreciate how direct this entrance feels.

Bab Madinah

Bab Madinah is named after the blessed city of Madinah, and the symbolism alone makes some pilgrims pause before entering. The gate faces the direction of the Prophet’s city, and many people walk through it with a quiet sense of love or longing. The entrance itself is modest, but the path inside feels gentle, with enough space to settle into the movement of the mosque.

Bab al-Quds

Named after Jerusalem, Bab al-Quds stands as a symbolic doorway more than a functional one. It connects pilgrims to the heritage of Al-Quds with nothing more than its name, reminding you that Masjid Al-Haram is deeply tied to Islamic history across continents.

Bab Shamiyah

Bab Shamiyah is named after the region of Al-Sham, the Levant, which historically included Syria, Jordan, Palestine, and Lebanon. This gate sits on the northern side, serving people approaching from older neighbourhoods. It has a steady flow but rarely becomes crowded, giving it a calm, practical feel.

Bab Nidwah

Bab Nidwah is named after Dar al-Nadwah, the historic meeting place of Quraysh leaders before Islam. The gate stands as a nod to the city’s political history. Today, Bab Nidwah remains a modest entrance, blending into the outer structure of the mosque. It’s used mostly by people who know the Haram well and prefer quieter paths.

Bab Quraish

Named after the Quraysh tribe, the tribe of the Prophet ﷺ, this gate sits near the northern end of the Sa’i area. The name alone ties it to Makkah’s earliest history, giving it a sense of belonging that feels almost emotional. Pilgrims using this gate often walk in with a gentle awareness of the past, even if they don’t say it out loud.

Bab Mina

Bab Mina takes its name from the valley of Mina, the place where millions of pilgrims gather during Hajj. The gate carries a sense of direction, a reminder of a place deeply tied to worship, sacrifice, and patience. Structurally, Bab Mina is a straightforward gate, neither grand nor hidden.

Bab Muhassib

Named after the Muhassib area between Mina and Arafat, Bab Muhassib carries the flavour of a name tied to the Hajj journey. The gate sits modestly on one of the outer sides of the Haram and offers a less crowded entryway for pilgrims who prefer avoiding busy corridors. It’s the type of gate you use when you want to soften the transition between the outside world and the mosque.

Bab Murad

Bab Murad means “Gate of Hope,” and there’s something tender about that. The name alone makes pilgrims pause, especially those walking in with prayers that feel heavy on their hearts. The gate is modest, located away from the main tourist flow, and used largely by those who know the mosque intimately.

Bab Mualah

Bab Mualah is named after Jannat al-Mu’alla, the historic cemetery where many of the Prophet’s family members are buried. The gate sits toward the northern side of the Haram, offering a clean, open entry that leads into calmer areas of the mosque.

Bab Hujoon

Bab Hujoon is named after Wadi al-Hujoon, an area with deep historical roots in Makkah. The gate is small, understated, and tucked into a quieter side of the mosque. Pilgrims who enter here often mention how refreshing it feels not to be swept immediately into a strong crowd. The simplicity of the gate makes it ideal for those who want a peaceful start to their worship.

Bab as-Salam

Bab as-Salam, the “Gate of Peace”, is one of the most beloved entrances in the Haram. The name alone calms you before you step inside. Located near the Sa’i path, this gate has long been associated with pilgrims entering with heartfelt duas. Many people around the world recognise it as the gate through which the Prophet ﷺ once re-entered the mosque after journeys, though its exact historical placement has changed.

Bab Aiesha (Gate 70)

Named after Aisha (RA), one of the most knowledgeable and respected women in Islam, this gate is one of four along the western side. It carries a soft honour in its name, and many pilgrims choose it because it feels familiar and easy to remember.

Bab Asma (Gate 71)

Named after Asma bint Abu Bakr (RA), this gate sits next to Bab Aiesha and shares its overall character, straightforward, simple, and widely used by pilgrims looking for a calm route inside. The gate offers a comfortable flow, especially during non-peak hours.

Bab Shubaika / Shabeikah (Gate 72)

Bab Shabeikah takes its name from the Shubaika district of old Makkah. Located on the western façade, this gate offers pilgrims an entry that feels balanced, not too busy, not too empty. Pilgrims often describe it as a “safe and steady” gate, particularly those arriving from the hotels near Jabal Omar.

Bab Yarmouk (Gate 73)

Named either after the famous Battle of Yarmouk or the Yarmouk region, this gate sits on the western stretch of the Haram. It’s one of the lesser-discussed gates but serves as a reliable entry point for pilgrims walking in from wider western districts. The movement through this gate is usually smooth, and it feels comfortable for those who prefer not to enter through the grander gates.

Bab Abu Bakr (Gate 74)

Named after Abu Bakr (RA), the first Caliph of Islam, Bab Abu Bakr is a simple, single-portal gate that sits on the south-western part of the mosque. It’s often used by pilgrims who want a quieter path inside without the large crowds around the major gates.

Bab Malik Fahad Stairs (Gate 78)

This gate isn’t famous for its look, it’s famous for its purpose. Bab Malik Fahad Stairs serves almost entirely as an access point to upper floors, especially useful during crowded seasons when the ground level becomes too full.

Bab Saeed bin Zaid (Gate 85)

Named after Saeed bin Zaid (RA), one of the early ten companions promised Paradise, this gate stands as a small tribute to a man of courage and faith. Pilgrims entering through this gate often come from southern walkways or quieter residential routes.

Bab Zayd bin Thabit (Gate 86)

Bab Zayd bin Thabit carries the name of the Prophet’s scribe, the man who recorded the Quranic revelation. That alone gives the gate a quiet nobility. It stands near Gate 85 and shares a similar layout, simple, clear, and easy to navigate. Pilgrims who enter here often find a comfortable rhythm as they merge into the mosque.

Bab Umm Hani (Gate 87)

Named after Umm Hani, a respected companion and relative of the Prophet ﷺ, this gate serves the south-western corner. It’s frequently used by women and families because the surrounding area tends to feel safer and more manageable. It leads smoothly into prayer spaces without the pressure found near major gates.

Bab Maimouna (Gate 88)

Named after Maimouna (RA), one of the blessed wives of the Prophet ﷺ, this gate mirrors the quiet, respectful tone of Bab Umm Hani. It is a gate used by families, women, and pilgrims who prefer quieter access points. The walking route inside is straightforward and leads to open prayer sections with little difficulty.

Bab Hijlah (Gate 89)

Bab Hijlah sits at the southern corner of the mosque and became known internationally after a 2020 incident where a vehicle struck the gate. Today it stands restored and calm, offering pilgrims a simple, low-pressure entry into the Haram.

Bab Hafsah (Gate 90)

Named after Hafsah (RA), another wife of the Prophet ﷺ, this gate sits directly beside Bab Hijlah. It shares the same gentle rhythm, modest crowds, steady walking pace, and easy transition into the mosque’s inner spaces.

Historic Gates of Masjid Al-Haram

Even in a mosque filled with modern design and wide marble corridors, certain historic gates still hold a presence that feels older than the walls around them. These gates remind you that millions walked here long before expansions reshaped the Haram.

- Original Bab Bani Shaybah (Historic Arch)

Before Masjid Al-Haram had tall entrances and modern doors, there stood a simple free-standing arch called Bab Bani Shaybah. It wasn’t a gate in today’s sense, just a stone arch that marked the entrance to the old neighbourhood of Bani Shaybah. Early Muslim historians like Al-Maqdisi recorded it as the most famous entryway of the 10th century. It stood close to the Kaaba until it was removed during Saudi expansions to make more space for tawaf.

- Bab as-Salam (Historic Position)

The current Bab as-Salam gate carries the name of a historic entrance that, according to many early sources, was once located much closer to the Kaaba. Pilgrims entering Makkah after long journeys would step through this gate as their first moment back in the Haram. Over time, expansions shifted their placement, but their emotional meaning remains.

- Bab al-Fatah (Historic Route of the Conquest)

Bab al-Fatah is the only historic gate whose story most pilgrims recognise instantly. Tradition holds that Prophet Muhammad ﷺ entered through this gate on the day of the Conquest of Makkah. Though the exact physical gate has been rebuilt, the name carries the weight of that moment.

Conclusion

Choosing the right gate in Masjid Al-Haram isn’t about knowing every doorway; it’s about knowing the one that feels right for your journey. Some pilgrims want the closest route to tawaf. Some want less crowd pressure. Some want a gate with history. And some simply want a path that feels gentle.

That’s why this long-form Masjid Al-Haram gates guide exists. To help you feel steady. And to remind you that every gate here, whether grand or humble, carries the footsteps of millions who came with the same prayer you carry now.

And when the moment comes, your feet will know where to go. Because now, you do too.

If you are planning Umrah from the UK and want clear guidance on hotels, walking distances, and the most suitable Masjid Al-Haram gates, Ziyuf Al Rahman provides guidance so you can focus on worship, not logistics.

Reference

https://madainproject.com/gates_of_masjid_al_haram

https://www.newsweek.com/massive-new-project-at-islams-largest-holy-site-what-to-know-10942510